In 2023 I travelled to the remote island of Santa Catalina in the Solomon Islands to capture the Wogasia Spear Fighting Festival, one of the most unique and least-documented cultural rituals in the world. In this new travel guide I share my experience attending Wogasia, diving into the cultural meaning behind the event, what it’s like on Santa Catalina and everything you need to know to visit this festival yourself.

I plant my feet on the sands of Aorigi at the break of dawn, with the resonating battle cries from spear-wielding warriors piercing through the rustling coconut trees.

To my left George Waimanu, the fiercest fighter in the Solomon Islands, brandishes his weapon and shield towards the sky, screaming out in daring furore.

Towards the east a wall of men, spread evenly from the sands into the sea, inch slowly towards Waimanu and the dozens of warriors adorned in clay that make up his Atawa tribe, anxiously waiting for the chilling call of a conch shell.

The air is electrified with trepidation. The large crowd of island residents are cheering their fellow tribesmen on, buzzing with anticipation for the first attack.

My eyes dart rapidly from left to right. I can’t shake the sensation that I’ve stumbled upon something extraordinary.

In a modern world that is caught in the whirlwind of innovation, what is unfolding before me is a window into a time-honoured culture that refuses to fade.

A shell is blown, Waimanu cheers and hurls his spear at his brother Robert, an elder in the opposing Amwea tribe, which is expertly deflected by his Hata shield.

The floodgates have opened, the battle has begun, and the sky turns hazy in a flurry of timber spears.

The final battle of Wogasia has begun, and I am in the epicentre of its chaotic storm.

Table of Contents

- The Wogasia Spear Fighting Festival – Solomon Islands’ Most Remarkable Cultural Event

- The Journey to Santa Catalina

- Our Arrival

- An Introduction to the Village

- The Morning Market

- Collecting the Conch Shells

- Collecting the Beater Sticks

- Fire and Fury Through the Village

- Songs til Sunrise

- The First Spear Fight

- A Morning of Rest and Preparation

- The Last Fight of Wogasia

- Returning to the Sea

- The Final Feast

- Wogasia Travel Guide – What, Where, When, Why and How

The Wogasia Spear Fighting Festival – Solomon Islands’ Most Remarkable Cultural Event

From the early days of intrepid explorers to awe-inspired youths thumbing through the yellow covers of National Geographic magazines, humans have always been in pursuit of the grand and the epic.

The call of the uncharted, the thrill of the unexpected, the joy of discovery — these are the lures that pull at our hearts and propel our feet onto untrodden paths.

Yes, even I, a humble traveller who has sought out a varied life of wandering adventure, have been consumed by this enduring quest.

Yet in this age of high-speed connections and geo-mapped corners, the search for such pristine experiences becomes akin to a cosmic treasure hunt.

The epic now evades our eager grasp, hiding beneath the cloak of the familiar and the well-known.

Scrolling through the endless feeds of social media we start to realise that what were once the most remote parts of this planet are now well documented. Even considered ‘trendy’ in some circumstances.

This doesn’t slow us down though. The challenge heightens, the journey stretches, the quest intensifies.

As a result, our thirst for the extraordinary takes us to the farthest flung corners of the world, to the edges of the earth, where the footprints of modernity have yet to tread.

It’s here, in the last vestiges of unspoiled wonder, that the spirit of epic travel experiences whispers to us, encouraging us to delve deeper into the embrace of the world’s unknown.

Having spent half of my life on a journey to step off the beaten path, I never thought to look close to home for an experience that would satisfy my yearning for adventure.

That all changed one March morning when a phone call came through asking if I was available to document Aorigi’s Wogasia Spear Fighting Festival, a fascinating and virtually unheard of cultural event in a remote corner of the Solomon Islands.

Despite being just a 3-hour flight from Brisbane, Australia, the Solomons are one of the least visited countries in the world, with less than 30,000 tourists stepping foot on the Pacific nation every year.

The stunning archipelago is already offbeat, and the handful of travellers that do come here are often in search of uncrowded surf breaks, untouched coral reefs or a quiet place to laze in a hammock with a loved one.

An ancient battle on an island with no scheduled transport, electricity or running water isn’t the typical drawcard for most visitors to the Solomons, and that was the reason I became so intrigued by the call.

“Wogasia is a series of rituals to wish for a good yam harvest for the next season,” Mike, a representative of Tourism Solomon Islands, told me on the phone.

“They fight with spears because the community is so small they don’t hold any grievances throughout the year, otherwise their society might fall apart.

“Instead they challenge anyone that they’ve had an issue with during the year to a spear fight on this one day only.

“Trust me, you’ll love it.”

After the phone call I dove into the vastness of the world wide web, and only came across a small number of stories and images from the fabled Wogasia Festival.

All of them vague, a brief recollection of a travel writer’s memories, but with enough allure to convince me that I couldn’t say no to this opportunity.

A few weeks later I boarded the international flight to Honiara, the capital of the Solomons, and embarked on one of the most remarkable travel experiences of my life.

The Journey to Santa Catalina

I spent a few days acclimatising in Honiara, visiting local markets, trekking to hidden waterfalls and purchasing supplies for my mission to Wogasia.

Garedd Porowai, a senior member of Tourism Solomon Islands, local legend and multiple veteran of Wogasia, was my personal guide and ensured that the logistics of my trip were well taken care of.

As I later found out, Wogasia, and the island of Santa Catalina (Aorigi’s common name) where it is held, isn’t the type of destination a foreigner can just show up to without local help.

The island has no airport or ferry terminal, there are no scheduled flights to its nearest neighbour Santa Ana, and permits need to be acquired before being granted access to this wild part of Solomon Islands’ Makira Province.

With Garedd and his team handling all the organisation, we packed our bags and headed to the domestic airport the day before the festival would start.

Our Wogasia group was made up of a very select number of people, just 7 in total, including 4 locals from the tourism board, airline and media – Garedd, Jenny, Crisinrita and Shaun – Johnny and Sam, 2 young Australians who were volunteering at the nation’s Institute of Sport, and myself.

A chartered Twin Otter plan operated by Solomon Airlines touched taxied down the runway towards the terminal and was refuelled and checked.

We claimed unallocated seats with hand-written boarding passes and buckled up for a mesmerising 1-hour 20-minute flight to Santa Ana, the closest port to Santa Catalina.

Soaring over the main island of Guadalcanal we soon passed over glistening coral atolls, turquoise lagoons and palm-speckled beaches before circling around Santa Ana and touching down on its grass runway.

Stepping out of the prop plane about a dozen locals welcomed us with smiles and waves.

We collected our luggage an watched the plane take off, leaving us behind with a tentative date of when it will be back.

Garedd had told us to expect a 30-minute walk from the top of the island down to the fishing village, but a rusted Toyota Hilux was waiting for us to transport us down the hill.

Piling into the tray we bounced through lush jungle and fruit plantations to the village, where over a hundred people were gathered to greet us visitors.

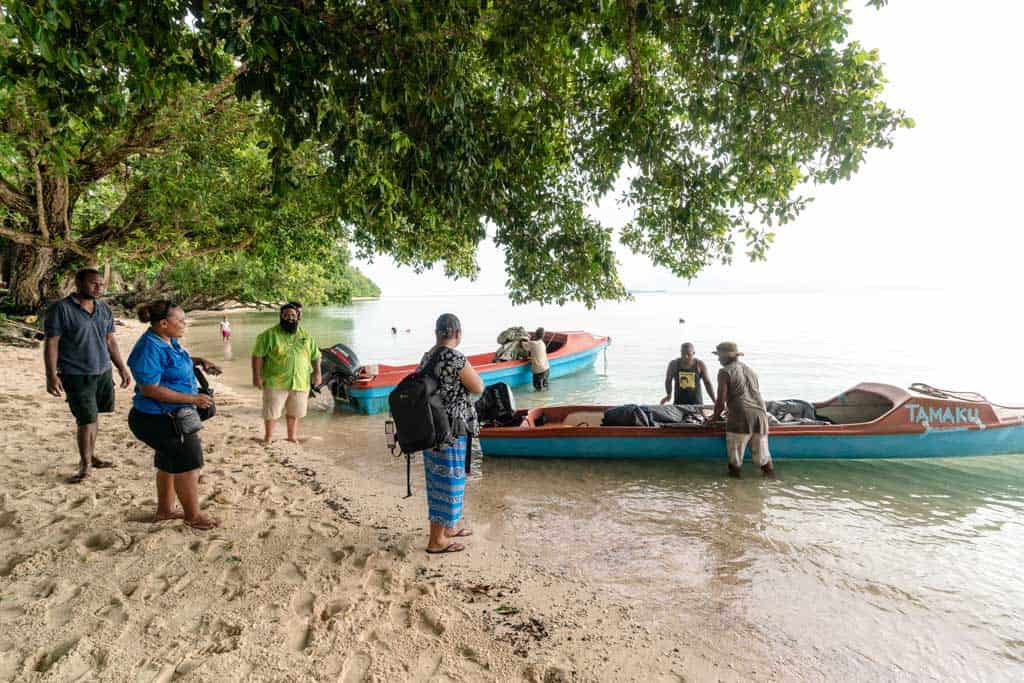

We relaxed on the beach, laughing along with the curious kids while Garedd negotiated a couple of small boats to take us across the sea to Santa Catalina.

Eventually with prices settled we jumped into the boats and motored off, waving goodbye to the island and eyes firmly fixed on our next destination.

Our Arrival

Approaching the swaying coconut trees of Santa Catalina induced a feeling of awe and mystery.

Spread out across the beach and filtering back through the jungle were a few hundred men, women and children, chatting excitedly as the visitors arrived, each one waving with beaming smiles.

Father Joseph, one of the village elders donned in a broad-leaf hat and peculiar high-vis t-shirt, greeted us with a traditional welcome, then led us to a family’s house for lunch.

We ate a large spread of fried fish, yams and rice, which would be our staple diet for the duration of our stay, downed by fresh coconuts plucked just an hour before.

Garedd greeted everybody that passed like an old friend. Having grown up on a nearby island, and working heavily in tourism and community development, he had become close to a lot of the locals here and was treated like an uncle.

After our group separated, I was taken to my host Father Jack’s place at the other end of the village and given a room to myself.

The bedroom was basic but had all I need – a bed with soft mattress and clean sheets, a firm pillow and a small table for placing my important items.

There was no electricity, lights in the room, nor a mosquito net, which I was told was not required as no mosquitos are found on Santa Catalina.

Nearby was a small outhouse with Western-style toilet, and an open-air room surrounded by plastic with a bucket for a shower.

It was simple, humble and somehow perfect in every way.

An Introduction to the Village

After getting settled I grabbed my camera and went for a walk through the settlements and houses of Santa Catalina.

I bumped into Garedd and asked what the plan was for the remainder of the day. He informed me that it was a day of rest, and that most people take it easy to prepare for the festivities that begin the following afternoon.

“A campfire on the beach would be cool,” I mused to Garedd. “Do the people here ever do that?”

“Hmm, not really,” Garedd said thoughtfully. “But yea, that would be cool!”

I continued my wanderings on the northern side of the island, where a couple of small villages spread out from east to west. Father Jack’s was in the centre, more or less, and back from the sea by 150 metres.

As I walked from settlement to settlement locals came out with broad grins and warm hellos, welcoming me to their island and showing me handicrafts or how they make food.

It was then that I met George Waimanu for the first time.

Garedd had been chatting with him under a lean-to shelter when I walked by.

“Jarryd, this is George, the best spear fighter on Santa Catalina! Come meet him.”

I jogged over to shake hands with George, a short man who stood just below my eyes.

He was lean and unassuming, but I could immediately sense his shrouded strength beneath his leather-like skin.

His eyes were gentle, and his kind smile beamed from his weathered face like a long lost friend.

George spoke little English, but language proved to be no barrier.

He welcomed me without condition, shaking my hand with both of his and appearing to be thrilled that a foreigner would come all this way to witness his beloved Wogasia.

We chatted back and forth, Garedd filling in the gaps for us, while I told him where I was from and what I did. George listened intently, with a look of concentration on his face which instantly broke into wild joy when it was translated for him.

I thanked George for his time, knowing it wouldn’t be the last I see of him on this small island.

I continued my tracks through the labyrinth of the village, and the kids quickly became the main attraction. Or more likely, I became their main attraction.

Everywhere I went the young children followed me like a shadow, laughing, giggling and posing for photos.

A few spoke the odd word of English, but for the most part they chatted to me in their own language and repeated what I said whenever I responded.

They led me to the beach and started playing games, running back and forth with a broken piece of thin plywood being used as a skimboard.

It was simple pleasures, the kind that have been forgotten back home by a younger generations who master iPads before they learn to kick a football, and it was magnificent to see.

Time went by quickly, and I noticed Garedd and a few of the locals gathering palm fronds and broken branches, dragging them into a pile on the beach.

“I asked about a campfire tonight and everyone thought it was great idea!” Garedd called out.

I looked at the towering bonfire, dense with dried palms and reaching well above head height.

“That’s going to be quite a fire!” I responded, then went off to find a few palm fronds to add to the collection.

As the sun set I met the rest of our small group back in the central village for dinner and coconuts.

After an early evening meal of fish and yam, we made our way back to the beach to find some of the locals gathered around the leaves.

One of the men came forward with a lit bundle of bark and sparked up the fire.

In moments the blaze licked its way through the pile and burst to the sky in huge dancing flames.

George Waimanu loudly emerged from the darkness, wearing a hat and skirt made of banana leaves, and wielding a shield and spear.

He ran in circles around the fire, waving his spear and crying out in chants and calls during the movements.

Some of children laughed at George’s vibrant display as he seemed to taunt the flames in twisting manoeuvres.

The fire flared up and burnt out quickly, and George was dripping with sweat.

Once he regained his breath he ran up to me and pointed to my camera. I showed him some of the photos I captured of his manic dance, and he cheered with delight.

A few of the men dragged the remaining unburnt fronds from the pile and kicked sand over the embers, extinguishing the fast and furious fire.

The spectators fizzled out much like the flames, and I followed suit, walking back to my hut and passing out to the blissful sound of silence.

READ MORE: Check out my guide to the best travel photography tips.

The Morning Market

I woke at sunrise, got dressed and head straight to the beach to sit and enjoy the morning blast of oranges and reds that mark the start of a new day.

To celebrate a handful of visitors being on their island, the artisans of Santa Catalina put on a morning market to showcase and sell their handmade carvings.

A range of beautiful handicrafts were available to purchase, from basic, small fishing hooks right up to intricate, shell-inlaid shields and elaborate head pieces.

The Santa Catalina artists lined the beach with the souvenirs on display, and I wandered back and forth chatting with the locals and checking out their works.

There was no pushiness or hustling from anyone, and each vendor seemed just as happy to show off their handicrafts without expecting a sale as they did when I eventually purchase more than my backpack could handle.

I bought 11 pieces of art in a variety of styles and sizes for less than AUD$200. It was so affordable I dared not barter, and I happily paid whatever the asking price was for each item.

The market only lasted an hour or so, then everybody packed up and returned to the village to get ready for the start of Wogasia.

Collecting the Conch Shells

The rest of the morning passed by lazily, broken up with a tasty lunch of curried chicken, fish and rice, and I continued my exploration of the village.

Families beckoned me to their homes to show me the food they were preparing for the next night’s feast, and even afforded me a few small samples.

George tracked me down and took me to his house, bringing me inside and proudly showing off some of his own handicrafts.

Besides being an expert spear fighter, Waimanu is also a skilled artisan with timber and stone.

He demonstrated how he carves shapes and lines into rock, and even offered me an elaborate wooden mask as a gift.

I left George’s house and returned to the shelter that had become our unofficial resting area to relax for another hour.

Garedd, the two Australians and I chatted idly over cups of tea when a hive of activity started to happen around 2pm.

The young men of Santa Catalina started to scurry off into the villages and jungle, returning with large conch shells that had been collected over years of Wogasia festivities.

Once enough were gathered two warriors and about a dozen young kids grabbed a shell each and wandered into the lapping sea, fully clothed, and started blowing the shells.

The sound was haunting and hypnotic, and within minutes the entire village came to the sands and watched as the boys and men blew and swayed and shouldered through the waves.

The conch shells were blown consistently for 30 minutes, in perfect unison and rhythm, when the eldest man in the group suddenly called out and they all returned to the beach.

They carefully cleaned their shells, scrubbing out any sand and dirt to ensure they were spotless for the next round of rituals.

Conch shells in hand, the boys and men wandered into the jungle and placed the shells in a pile next to a large rock, then disappeared to get changed.

Collecting the Beater Sticks

As the men filtered through the village the women then went foraging through the forest in search of ‘beater sticks’ – long, thin branches that would be used later in the evening.

Each woman collected at least one stick, then placed them in a pile amongst dense shrubs on the western end of the village.

The afternoon rituals were over, and everybody returned to their homes to rest before nightfall.

Our hosts cooked an early dinner, and Garedd told me that we had a few hours spare before we’d hear the sound of conch shells blown again.

“When they blow the shells there’s no stopping until after Wogasia,” Garedd warned me.

I made a decision to refuel my energy bank while I had the chance. Alarm set for midnight, I then headed back to my room just after sunset to get some sleep.

Fire and Fury Through the Village

I woke at midnight and headed to our dining hut to find Garedd and Johnny chatting quietly and looking extremely sleep-deprived.

They had decided to pull an all-nighter, and the bags under their eyes warned that their decision may not have been the smartest one.

We made a fresh batch of instant coffee to wake us up and sat around for a few hours more, still with no movement in the village.

“They need to wait until a star moves into a particular spot in the sky before the next part starts,” Garedd informed us.

I peeked out from shelter and stared through the palm trees, seeing nothing but dense cloud. With no stars visible, it would be anyone’s guess as to when the village elders felt it was the right time to start.

Just after 2am we heard the first conch shell echo through the trees.

We ran to the far side of the village and found the men starting to gather in a large crowd.

The sound of one conch shell turned into two, and then multiplied exponentially until the unison of horns became deafening.

The entire island was now awake, and many of the locals picked up beater sticks from the pile while the young ones and teenagers ran off into the dark.

“Let’s go to the main square,” Garedd suggested, and we quickly shuffled off before the chaos began.

We retreated into the darkness towards the centre of the village, meeting at the edge of a large, open square, and waited for the spectacle to begin.

Garedd and I chatted quietly with a few older ladies when we heard the sudden cries of an excited stampede reverberating through the timber shacks.

The noise was furious and distant, and rose sharply in volume as the unseen crowd neared our empty square.

At one point the sound was all around us, pulsating through our bones, when shadows and shrieks emerged from the endless night.

As the silhouettes of warriors appeared flaming embers flew through the air, hurled by invisible teenagers hiding from the onslaught.

Scores of men and women burst into the scene, screaming and whacking the flaming missiles on the ground with intense power.

The explosions of fire illuminated their faces amongst the blackness, and the entire village seemed to be under attack by the beaters.

Mischievous children hurled their own mischievous projectiles – buckets of fish guts that quickly coated all who entered the battlefield.

This moment would have been deathly terrifying, if it weren’t for the subtle tones of joy underlying their screams and the cheeky smiles that beamed as the embers lit up the square.

After only a minute or two, the crowd disappeared, charging through the next settlement leaving broken sticks and small, glowing coals in their wake.

I remained motionless for a few moments more, trying to process what I had just witnessed.

In the distance the sounds of screaming subsided, and it seemed as though the charge had come to an end.

Garedd smiled. He had seen this many times before, and yet clearly found it as powerful and intimidating as I had.

“They use their sticks to beat the evil spirits out of the earth,” he told me, and it all started to make sense.

“Let’s go to the beach,” he said, and we wandered off past the villages towards the eastern end of the island.

Songs til Sunrise

We headed to the ocean to meet the crowd, and the conch shells echoed out again.

Everybody ran to the edge of the sea and threw their beater sticks into the waves, symbolically sending the evil spirits away from their land and clearing the soil for a productive harvest.

The beater sticks floated on the surface, and the whackers came together in unison.

Most were covered in fish blood and organs, and a few had been accidentally hit with the sticks amongst the attack, but nobody seemed to be agitated by the injuries.

It was about 3am now, and the group wandered east into the darkness.

Once we made it to the end of the beach everybody took a place seated in the sand, and the children started singing a song about the rising sun and pudding.

Betelnut was passed around, acting as a strong stimulant to keep the adults awake.

Chewing and spitting the red juice into the ground, the song continued on repeat for many hours.

I snuck away to find a patch of sand to lay on, staring up at the stars and resting for 30 minutes while drifting in and out of consciousness to the chanting echoing in the night.

When the faint glow of daylight started to materialise on the horizon the singing stopped, and the women gathered in a large group before hiking into the jungle.

I found Garedd chatting with a few of the village elders. “They’re going to go pick some flowers from a special tree,” he told me. “When they come back the men can start their first fight.”

The sky slowly changed from black to blue to purple, and as the new day neared the islanders moved to a wide patch of beach in anticipation of the women’s return.

The First Spear Fight

We stood around underneath the cover of palms while men walked off to prepare for the upcoming fight.

The sun broke through the low clouds on the horizon and the women returned quietly with the flowers, signalling that Wogasia could now continue.

The warriors’ clothes were swapped for traditional headpieces and leaf skirts, and many asked me to take their photos before they separated into two warring tribes.

On the beach the audience grew in size and we stood in heightened anticipation for what would come next.

Suddenly George Waimanu charged onto the beach, thrusting his spear and shield into the air and taunting the invisible enemy to the east.

The crowd cheered, and George was joined by two more warriors, dancing, screaming and spinning.

At this challenge we looked towards the sun and saw the Amwea tribe emerge from the jungle, spreading out from the edge of palm trees and far into the ocean.

They approached slowly and determinedly, calling back their own cries of war.

As they neared George and his fighters were joined by dozens more, and one of the elders wandered onto the battlefield, drawing a line in the sand with his foot.

The two tribes were now just 20 metres apart, head to head from sand to sea, and itching to begin.

A conch shell blew from the crowd and George hurled the first spear directly at his brother Robert, who was standing amongst the other tribe.

There was no holding back now. Spears flew across the beach with immense velocity, mostly being deflected by shields or hitting the sand, but with some striking their targets with audible thumps.

More than a few also veered off course, nearly taking out members of the crowd who were cheering passionately.

The craziness of the fight in front of me continued for around 10 minutes, spears interchangeably flying back and forth with the energy never wavering.

Finally a chief ran into the middle of the battle, declaring that the fight was over.

George and Robert met in the middle, screaming and taunting their spears at each other, before eventually retreating.

The first spear fight of Wogasia was done, and the animosity faded as quickly as it had appeared.

The two tribes came together and laughed, checking to make sure everyone was ok and slapping each other on the backs or shaking hands.

Warriors returned to being brothers, and the atmosphere morphed into jovial conversations.

The strongest fighters from each tribe posed for a photo and then we all headed back to the villages, passing beneath an elevated pole held high by two warriors which symbolised the separation of the battle and brotherhood.

A Morning of Rest and Preparation

Returning to the village everybody made their way back to their homes to recover from the long night and clean themselves of sweat and fish oil.

I had a light breakfast and a few mugs of instant coffee, relaxing by my hut for a few hours and watching the locals come and go.

Just before lunch I went for a walk and was called over to the homes of many families, who wanted to show me the various meals they were preparing for the final feast that night.

Coconut pudding and fermented fish would be on tonight’s menu, and I was offered a few tasters as a treat.

The morning passed by slowly, which suited me fine in my sleep-deprived state, and I bounced between the shade of the dining hut and the beach, where energetic kids played games without a care in the world.

Our hosts made us a delicious lunch of fish, rice and fresh fruit, and we kicked back waiting for the final event to begin.

The Last Fight of Wogasia

There was movement amongst the village and people started filtering towards the main settlement.

We joined the crowd and heard that the boys and men of Santa Catalina had ventured into the hills to camouflage themselves in clay before the fight.

Garedd led us to the edge of the village and we sought shelter behind a small house to escape the unrelenting heat of the day.

We waited almost 30 minutes when without warning over a hundred boys coated head to toe in mud flooded down from the hills, spears in hand, shrieking hysterically.

The shock of their appearance hit us quickly and unexpectedly, and Garedd led me to the front of the line to face the young warriors.

Their army grew larger and more fierce, and behind the kids the adult men appeared in support with the look of battle etched firmly on their faces.

The crowd surged towards the beach in 50m increments, and I was caught up in the stampede.

Backing away I couldn’t escape the onslaught, and I had to dart into the bushes to avoid the charge.

When the men paused to prepare for their final push to the sea I ran to the beach to find over 50 women being dressed in head-to-toe banana leaf costumes, called mwako mwakos.

I stopped to admire the intricate work being applied to the costumes, but was distracted by the sound of conch shells and screams coming from further down the beach.

Looking across there was a scrum of people gathering beyond the palm trees, and I bolted to catch up to them.

When I arrived the crowd was thick and I stood on my toes to try and get a glimpse of the battle.

Some of the locals near me noticed I was trying to see the action, and they ushered me to follow them, parting the crowd and taking me to the front of the mosh pit.

Breaking through into open space, I regained my balance just in time to see the first spear thrown.

The intensity of the final battle was on an entirely different level to the fight I had witnessed in the morning.

The spectators were more energised and the warriors were not holding back.

Spears criss-crossed through the air as fast as javelins, striking some of the men in the torso and legs.

Cries of pain echoed above the furious screams, before the wounded fighters would shake away the injury, pick up another spear and hurl it back faster than ever.

The ferocious battle lasted only a few minutes before two chiefs ran into the strike zone and yelled for the fight to end.

Like a switch, the spear-throwing ceased and George, Robert and Max ran forward once more to taunt each other.

They were dripping with sweat, and the exhaustion in their eyes was evident, but they still looked as fearless as ever.

Finally they lowered their spears and shields and retreated.

Grievances were cleared, brotherhood returned, and the war was over…until next year.

Returning to the Sea

All the men of Santa Catalina, those who fought and those who watched, came together in jovial friendship and chatted fondly in the shade of soaring palms.

The conch shells continued, men swayed and danced, and a few elders sung out words of encouragement and brotherhood.

On the other side the women dressed in their mwako mwakos formed a single line and wrapped themselves around the edges of the village square.

Their costumes were both fascinating and intimidating, with only the hands and feet of the women exposed.

I found Garedd and asked why they were dressed like that.

“Banana leaves are very important on Santa Catalina,” he shared, while keeping an eye on the crowd.

“Food is wrapped in banana leaves for cooking and they use them for plates as well. All the women are also holding a stick and a stone, which they use every day when cooking too. Wearing them all is like asking for a blessing for good food this year.”

I wandered up and down the line of women, snapping a few photos and admiring the details in the weaving of the costumes.

Then the woman at the front of the line screamed out, turned and ran through the village, with each costumed lady bolting behind at relentless speed.

Like a long green snake on attack, the women charged down the dirt path between the ocean and the village. The crowd followed, and I tried my best to keep up with them.

Minutes later they reached another beach and ran into the ocean, stripping off their costumes in the sea revealing their normal clothes underneath.

The banana leaves spread out far and wide, lapping back to shore with the crescent waves.

The warriors soon joined us at the beach, and they took turns running down the sand to throw their spears into the ocean.

Young boys sped ahead, diving into the sea and splashing each other with glee.

With so much fury, grievances and spirits held in those spears, this was the final act to send all bad omens off the island.

It was a beautiful and powerful scene, with the women laughing and splashing each other amongst the banana leaves and the men hurling hostility as far away as their weathered and weakened arms would allow.

15 minutes later the final spear landed in the sea, the last person exited the water, and everybody dispersed back to their homes.

The rituals were over. Everything that could be done to wish for a bountiful harvest was finished, and with the battle between men completed the upcoming year would be as uplifting and communal as the spirits would allow amongst the Aorigi brothers.

All that was left to do was feast.

The Final Feast

As the sun started to set the entire island separated, with every man and boy making their way to one settlement and every woman and girl heading to another.

The food that was prepared over the past few days was now served communal style, sitting on the bare earth and sharing the 6-month pudding, dried fish and yams.

Laughter bounced off the timber homes edging the square. I looked around and saw only beaming, tired smiles on the faces of the men.

The next morning I would jump on a fishing boat and leave Santa Catalina, beginning a long journey back to my own home.

I’d be returning with the warmth and hospitality of the Aorigi villagers lodged in my heart, and a glorious insight into one of the world’s most interesting cultural events.

Perhaps I too would learn to not let grievances occupy my inner thoughts throughout the year.

My desire to discover the extravagant and epic had been fulfilled. Beneath the swaying palm trees on a remote corner of the Solomons I’d quenched my thirst for an adventure in a way that few had ever seen.

George Waimanu came up to me with his illuminating smile and offered me a piece of dried fish.

He spoke to me in his native tongue and I turned to Garedd to ask what he said.

“He wants you to come back next year. You’re in his ‘Atawa’ tribe now, and he wants you to be part of the next Wogasia.”

I returned his vibrant smile. “Of course George, I’ll come back again. As long as you promise not to fight me!”

George burst into deep, honest laughter, shook my hand between his own and joined his brothers back at the feast.

I suppose I better start brushing up on my spear fighting skills.

Wogasia Travel Guide – What, Where, When, Why and How

Attending the Wogasia Spear Fighting Festival in the Solomon Islands is one of the world’s greatest cultural experiences, and after 15 years chasing my own adventures remains one of my top travel moments.

Visiting Santa Catalina and taking part in Wogasia though is a true off-the-beaten-path escapade, and requires planning and local assistance to be granted access.

If you have read my experience of Wogasia and would love to attend the festival yourself, I have put together this comprehensive guide to everything you need to know.

What is Wogasia?

Wogasia is a vibrant relic of the old Aorigi culture, which continues to be a living tradition on the island to this day.

It’s a sacred celebration of rebirth and fertility, routinely observed each year during the final week of May or the initial days of June, with its exact timing dictated by the new moon lunar cycle.

This festival signifies the conclusion of the yam harvest, presenting a rich tapestry of the Aorigi people’s enduring connection with nature and their past.

Wogasia incorporates a number of rituals held throughout the 36ish hours that it occurs, and while the most dramatic one is the spear fight, there are a lot of other important moments to experience.

What is the Purpose of the Spear Fight?

Spears have been used by warriors of the Pacfic for centuries, and along with clubs have long been the weapon of choice for warring tribes.

Today on Aorigi locals keep spears for ceremonial purposes and to be used on the annual Wogasia festival.

With just 2000 people living on Santa Catalina the community is tight-knit and dependent on a civilised society.

If anger, fights or arguments were to take hold, the community runs the risk of being torn apart in such a remote place.

Of course disagreements do happen, but to ensure society operates smoothly there is an unwritten rule on the island that nobody can hold grudges or act on their grievances with fellow villagers.

Instead what the men do is continue their lives in harmony, and use the day of Wogasia as a way to deal with their issues.

Wogasia gives an opportunity for a man to challenge another man to a spear fight to settle problems.

The spears are blunted to not cause serious harm, although the impact can result in minor injuries.

Each man can also only be challenged once each year, so there is no multiple individual battles happening during the fight.

Once the spear fight is concluded there are no winners or losers. Rather the grievances are deemed to be dealt with and must be forgotten about, allowing the community to move forward.

How to Get to Santa Catalina

Santa Catalina is a remote island found in the Makira Province, far from Honiara in the eastern part of the Solomon Islands

The traditional name is Aorigi, with “a” meaning island and “rigi” meaning very tiny.

The trip to Santa Catalina is an intrepid journey in itself, and requires both a sense of adventure and a bit of logistical planning with assistance from the airline and tourism board.

There’s no airport on Santa Catalina, so instead you need to fly to Santa Ana, the next closest island.

Solomon Airlines, the national carrier, doesn’t offer regularly scheduled flights to Santa Ana due to lack of demand.

The only option is to organise a charter flight with Solomon Airlines on one of their Twin Otter propeller aircraft, or coordinate your trip here with a charter that is already booked.

The easiest way to organise this flight is to get in touch with the team at Tourism Solomon Islands, or with Jenny Lobo at Solomon Airlines (jlobo@flysolomons.com.sb).

Once you have secured your flight you’ll depart Honiara on the 1.5-hour low-altitude trip to Santa Ana, flying over stunning coral atolls and the mountainous, jungle landscapes of the archipelago.

Boasting a long, grass strip for a runway and an open-air shelter for a terminal, it’d be a bit of a stretch to say Santa Ana has much of an airport, but that makes it even more adventurous when you eventually touch down.

From the air strip you’ll need to make your way down to the main fishing village on Santa Ana.

If you’re lucky, or somebody from Solomon Airlines or the tourism board has reached out ahead of time, one of the locals will be waiting for your flight with an old, beat-up Toyota Hilux to transport you and your luggage down to the village.

If the ride hasn’t arrived though you’ll need to walk down the dirt road through lush forest for about 30 minutes.

At the village you’ll find a welcoming collection of fisherman and smiling children excited to see you, and a number of boats docked at the beach.

Negotiate a price with the fisherman for a trip to Santa Catalina, which is only 25 minutes away across the sea, and head off.

Accommodation on Santa Catalina

You won’t find a 5-star Hilton on the remote island of Santa Catalina, but what you will find in my opinion is so much better.

The options for accommodation on Santa Catalina are limited to cosy rooms in a local family’s home, and as tourism has slowly started to ramp up here (and when we say ramp up, that’s for the 20 or so foreigners a year who visit), the guesthouses have improved in comfort and privacy.

If you haven’t already organised your trip to Wogasia or Santa Catalina ahead of time with the tourism board, you’ll have to chat with one of the local chiefs about which family you can stay with.

Don’t worry, you won’t be left stranded here without a roof over your head. You will be well taken care of from the moment you step foot on Santa Catalina.

Assuming you’re travelling as a group though, the chiefs would have already figured out which family you will be living with during your time here.

You will be offered a private room inside a small timber shack with a single bed, thin mattress and clean sheets.

There are no ensuites here. Rather you’ll use the outhouse equipped with Western-style toilet, flushed with a bucket due to no running water, in a communal area for the family.

A bucket shower is available and is enclosed with plastic to create some privacy.

The rooms don’t have locks but some doors do have latches where you can put a padlock.

Not that theft is a problem here, and the entire time I stayed on the island I just closed my door without worrying about a lock.

There’s no mosquitos on the island, so no need for a mosquito net either. But the rooms aren’t completely sealed, so don’t be surprised if small, harmless insects get inside.

Ultimately the accommodation on Santa Catalina is basic, yet comfortable, and really is all you need.

Food

What can you expect to eat in Santa Catalina?

The island lives mostly off the land and sea, with only a few provisions such as rice regularly brought in from elsewhere.

As a result the food is basic yet nuturious, served morning, noon and night, with a variety of staples such as bananas, papaya, yams, potatoes, rice, fresh fish and the occasional chicken meal if you’re lucky.

There are no shortage of coconuts either, and I often found piles of fresh coconuts on a table with a machete that were free to take.

Meals are cooked by the women of the guesthouses and you will either be eating with your host family or in an assigned shelter for groups.

Vegetarians and vegans will have a hard time getting protein here, so if you would like to stick to a strict diet it is best to bring your own supplements as well.

Personally I am a vegetarian, but made exceptions to eat fish and chicken on Santa Catalina out of respect for my hosts and the knowledge that this is as farm to table as you can get.

It’s also a good idea to bring some other groceries with you from Honiara such as instant coffee or tea and snacks.

3 meals a day are included with your stay.

Life in the Village

There is somehow both a lot and not much to do in the villages of Santa Catalina.

With no power or phone service days are spent playing games with the children, hanging out at the beach, spending time with your hosts or other families, cooking, learning how to kite fish, snorkelling (if the weather is nice) and simply kicking back with a book.

When the festival is on though there is little down time, and you’ll be extremely busy joining in the activities and watching the rituals.

Life is simple and relaxed here, and some of my favourite memories were formed by just walking around chatting with the villagers.

How Much Does it Cost to Attend Wogasia?

There is no ‘set fee’ to attend Wogasia, but there are a variety of logistics, bookings and permits that need to be taken care of before you can visit, which do add up in cost.

Expect to pay about $6,000 SBD (USD$700 or AUD$1,100) total for your charter flights from Honiara, boat transport, accommodation, meals and access fees for the 3 days and nights.

When is Wogasia 2024?

We have just received confirmation from Chief Silas that the dates for the next Wogasia will be June 2nd and 3rd, 2024.

Where to Book Wogasia?

If you would like to attend Wogasia it is best to speak directly with Garedd Porowai from Tourism Solomon Islands.

He can take care of everything you need to visit Santa Catalina and attend to Wogasia.

Numbers for 2024 will be strictly limited to 15 visitors maximum. No exceptions.

Get in touch with Garedd via email: garedd.porowai@tourismsolomons.com.sb