Weighed down with dive gear and tanks, we lumber down a rough concrete stairway in the jungle towards a shallow cave in the limestone rock.

We’re sweltering in full-body wetsuits. Humidity hugs us like a soggy blanket and mosquitoes buzz our heads and hands, the only skin unprotected by neoprene. We’re starting to wonder whether our preconceived, and perhaps slightly romanticised, idea of cenote diving might be a few degrees off.

At the base of the stairs, a small natural pool greets us under the rocky overhang. The water is crystal clear and teeming with little black catfish.

It’s beautiful, but it doesn’t look like a place to go scuba diving.

We’re at the Tajma Ha cenote, halfway between the beachside towns of Playa del Carmen and Tulum, on Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula. The Yucatán is famous for its impressive Mayan ruins, white sand beaches, and its cenotes – natural, water-filled sinkholes that honeycomb the flat, limestone peninsula.

It’s also renowned as the site of one of the planet’s most catastrophic events: an asteroid impact 65 million years ago that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. Today, cenotes cluster along the ancient underground rim of the 180-kilometre-wide Chicxulub crater, and can be found across much of the Yucatán peninsula.

At Tajma Ha, our guide Sarah, a certified cave diver, grabs hold of a rope and climbs down into the translucent pool, waving for us to follow. Beneath the surface, we gather at a small pink arrow on the cenote floor. It points towards the back of the pool, where a cavern line disappears between the rocks.

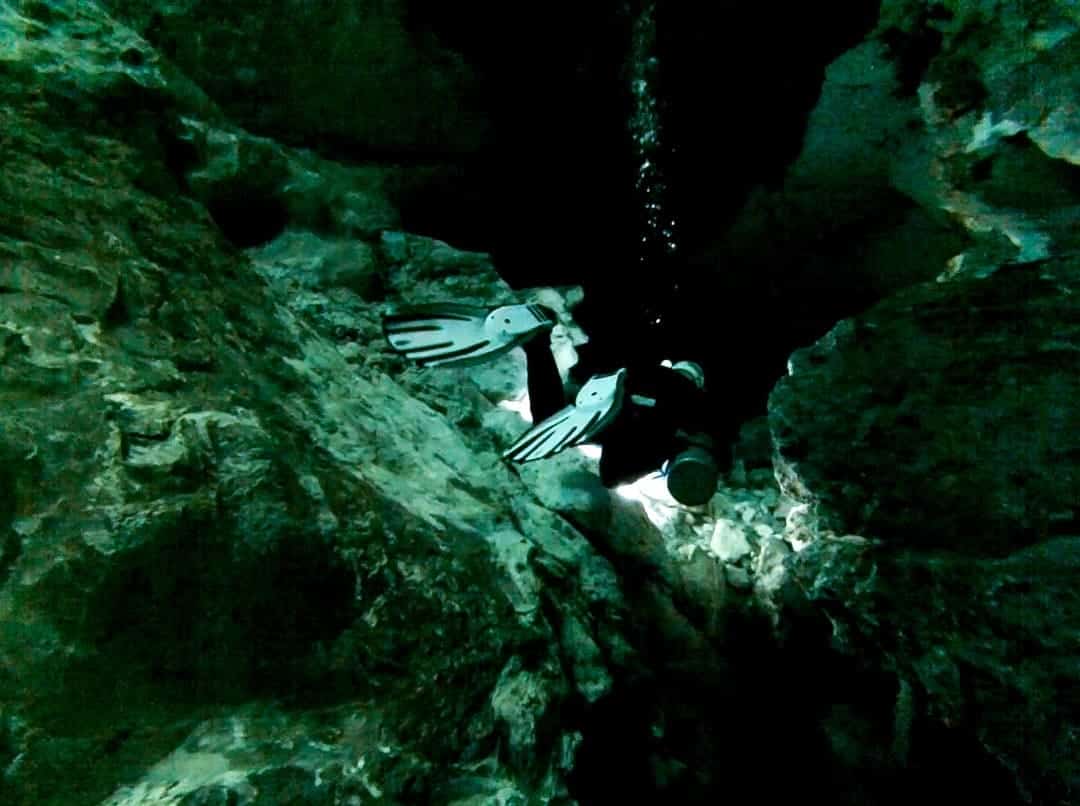

We’ve been briefed on what to expect over the next forty-five minutes of diving, but as we kick after Sarah, we’re still unconvinced there’s even an exit to our little pond. Then we pass through a small fissure, and everything changes.

Beyond the crevasse, we slowly drift into the darkness of what feels like a large open space. Sarah waves her torch, revealing the curved walls and low ceiling of a wide limestone passageway ahead of us.

To our right, a torch beam catches a startling skull-and-crossbones, a warning sign to divers not to pass into the vast black nothing beyond.

It’s the first of many breath-catching moments as we set out on one of the most extraordinary dives we’ve ever made, a journey through the watery realm beneath the Yucatán jungle.

Our pace is slow and relaxed, like the black catfish that occasionally cruise by just inches from our masks. Now and then, Sarah circles her light around shell fossils embedded in the chalky limestone, remnants of a prehistoric reef.

Ancient stalagmites rise from the floor and catch in our torch beams, while stalactites grip the low ceilings. In the dim light and narrow passages, we’re hyper aware of our surroundings, and our buoyancy control.

The water is like glass. There’s very little current and, unlike the ocean, it’s completely silent. The stillness is broken only by the sound of our slow, mechanical breathing.

At times, it feels like we’re floating through the air in a kind of alternate, noiseless, torch-lit universe. It’s surreal and intense. Which is fitting. We are, after all, diving through the gateway to Xibalba, the underworld of the ancient Mayans.

Cenotes were once believed to be the dwelling places of the Mayan rain god, Chaac. Artefacts found in some cenotes, like golden objects, jewellery, even human bones, suggest the agricultural Mayans made ritual sacrifice to their vital rain-maker deity.

Even the word ‘cenote’ comes from a Mayan word, dzonot, meaning a natural well.

At Tajma Ha, a shimmering glow appears through the darkness, transforming into an iridescent curtain of light as we approach Sugarbowl, our next, linked cenote. We surface briefly into the circular cavern, open to the sky through a hole in the ceiling. Bats flit above our heads and the calls of Motmot birds echo around the chamber.

Further on, we descend to a deeper part of the tunnel network. Sarah casts her torch onto a halocline, the boundary between the fresh rainwater of the cenote system, and the dense, heavier salt water that has seeped in from the coastal fringe of the peninsula.

From above, the halocline shimmers like sunlight reflecting off a lake, only this lake is under the water. Dropping into it, the world blurs and swirls around us, dream-like and slightly disorienting.

We’re familiar with this hazy, psychedelic halocline effect though, having cut our cenote diving teeth earlier in the day at Jardine del Eden.

One of the Yucatán’s most popular cenotes, Jardine del Eden is vast, beautiful and open to the sky. On this day, the first sunny day in a week, we arrived to a carpark jammed with excited families, and scuba diving students gearing up for their pool training.

We hit the water quickly, swimming past teeming fish and green, algae-covered rocks before descending into a tranquil underground passage connecting with the nearby Coral cenote.

Finning through the short tunnel, we were suddenly treated to a spectacular light show as the sun’s refracted rays pierced the water of the cenote ahead. It was like stumbling across a submerged stage, illuminated by a thousand beams of light.

As our eyes adjusted, more details were revealed, like clustering tree roots and fish darting between rocks, but our eyes were constantly drawn back to the dazzling beams. Later, as we made our way back to Jardine del Eden, we emerged to a sea of legs dangling in the water above, and surfaced to the shrieks and splashes of dozens of day-trippers.

The cenote diving at Jardine del Eden was slow and relaxed, with an easy point of entry, and a less-challenging underwater environment: the perfect introduction to this singular scuba diving experience.

Back at Tajma Ha, the dive is proving more demanding, with plenty of narrow swim-throughs, and constant equalising as our depth shifts up and down through the passageways and caverns. It’s tricky and exciting, but we’re grateful for the primer we’ve had at Jardine del Eden.

As we near the end of our Tajma Ha dive, we pause for another surface, this time in a partially-filled cavern with three small holes in the ceiling.

On bright days like this one, the sun lasers through the openings to form three intense shafts of dazzling blue light in the water below, giving the room its name: Points of Light. It’s a scene straight out of the Star Trek transporter room. One we’ll need to sear into our memories. Moments before arriving, our camera battery gives out.

Surfacing through the beams, we float for a few precious moments in the cavern, taking in the ambience. The only legs dangling here are our own. A few minutes later, we swim through a crevasse into the shallow pool where we started. We’re buzzing with adrenaline as we haul out of the water, already talking about future cenote diving opportunities.

As we turn to climb the stairs, we both take one last look at the small pool of water under the limestone overhang. It really doesn’t look like a place to go scuba diving.

But it’s one of the most magical scuba dives we’ve ever done.

Things To Know About Cenote Diving In Mexico

Cenote diving on Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula is easy to organise, with dozens of operators running trips out of Tulum, Playa del Carmen and Cancun.

Trips usually include two cenote dives, and there are a plenty of cenotes to choose from. They range in complexity from easy dives for beginners through to dives requiring Cave Diver certification.